Walking along Ferry Street it is impossible to miss the Brazilian presence in the neighborhood. Portuguese conversations conducted in a Brazilian accent provide the soundtrack to the Brazilian clothing stores that dot the street and the Brazilian products on the shelves of the grocery stores. The Brazilian restaurants along Ferry — Suave Sabor, Casa Nova Grill, Brasilia Grill and the 24-hour Altas Horas Lanches — are a small sample of the larger Brazilian food landscape that has spread throughout the Ironbound neighborhood in which Ferry Street serves as the commercial, cultural and culinary hub.

Sabor Unido, a relatively recent addition to the landscape, is located steps off Ferry on Jefferson Street. Despite being situated at the heart of the Ironbound, the location provides a degree of removal from the noise of cars and loud music characteristic of Ferry Street. Its humble appearance makes the restaurant easy to pass by without noticing what lies behind the modest facade. When the weather allows, Sabor Unido announces its presence on the street through the red umbrellas, black furniture, and planted pots that line the building's exterior, expanding the restaurant’s territory beyond its walls and onto the public space of the sidewalk.

On a warm summer’s day there is a good chance you'll find Luiz Campos in front of the restaurant, bussing tables, arranging the furniture or sitting in a chair chatting and cracking jokes with some of the regular customers. Son of the Brazilian couple who run the restaurant, Luiz also waits tables, makes deliveries, and assists his father with other aspects of the business. In our first visit to Sabor Unido it was Luiz who greeted us, helped us navigate the menu, and with an infectious smile told us about their family-run business.

The warmth and friendly vibe that characterize the family is also felt in the interior design of the restaurant. The restaurant's merging of Brazilian and Portuguese cuisine is mirrored on the walls which generate hybrid cultural memories and invoke nostalgia. Two blue Macaws, the lovebirds featured in the animated film "Rio”, and the statue of "Christ the Redeemer," the globally recognizable icon of Rio de Janeiro, are placed beside a painting of Lisbon's Belém Tower, a symbol of Portuguese maritime expeditions at the height of their imperial power. The same wall features two iconic examples of Portuguese arts and crafts — the Rooster of Barcelos and a painting of blue and white azulejo ceramic tilework — that, like the fado music that can be heard throughout the neighborhood, are resonant signifiers of Portuguese identity.

Although Portuguese and Brazilian iconography share the walls, the television is most often tuned to Brazilian channels. Luiz’s parents Orlando and Silvana dance in Samba competitions, and the music in the restaurant skews toward Brazilian dance music. The customers are primarily Brazilian and Portuguese, though in our several visits to the restaurant we also saw Latinx families and African Americans, as well as white professionals who wore suits and sat in the quieter, more private side spaces of the restaurant.

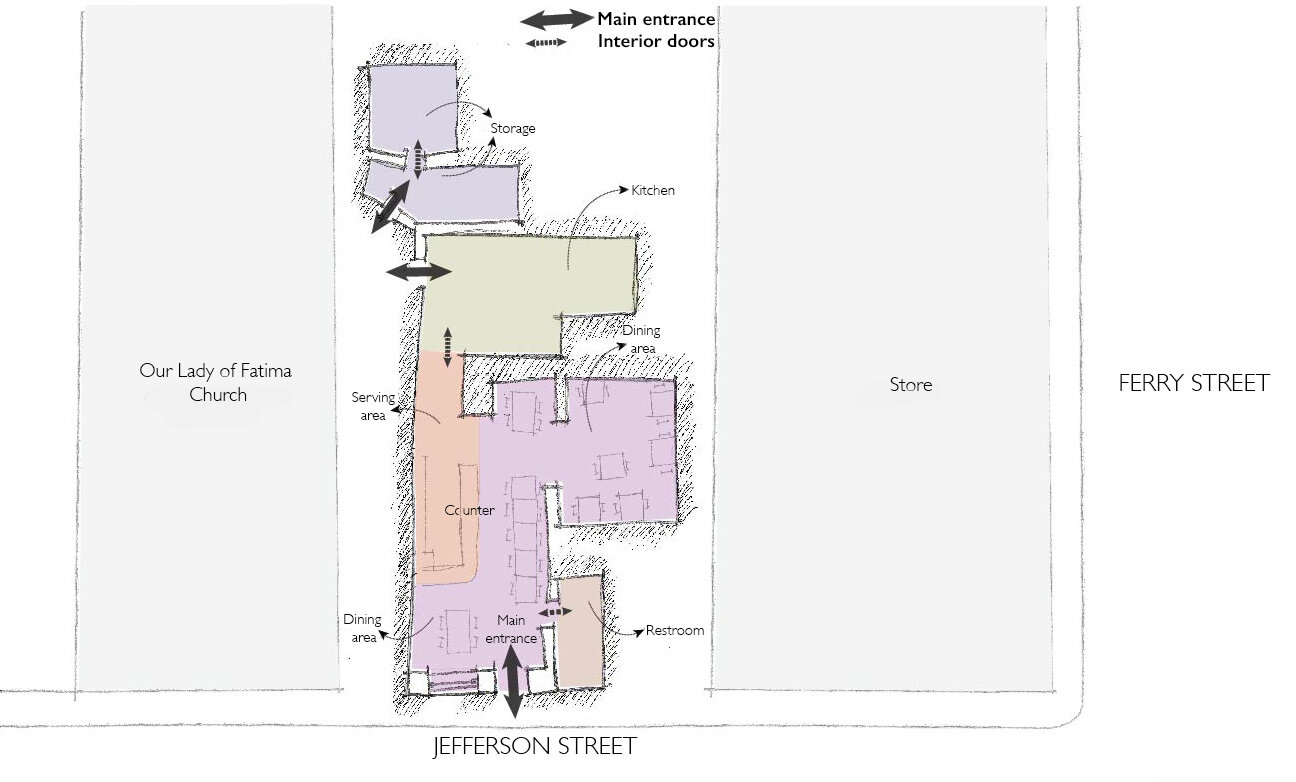

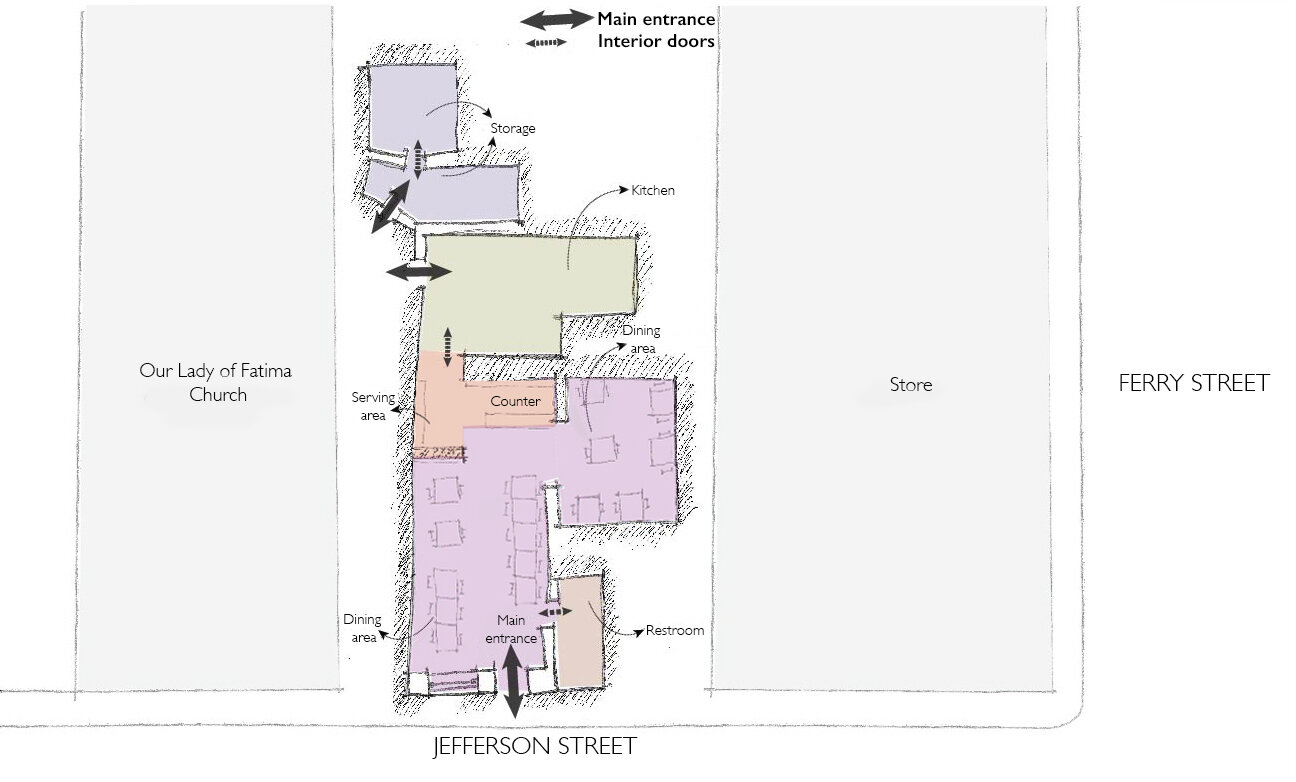

The counter is a prime space of interaction in the restaurant. Regulars who stop by for a meal often approach the counter to order their food, sometimes without looking at the menu. Others sit at the tables across from the counter and engage in conversations with Luiz and Orlando while eating. The father and son’s constant presence and the cozy atmosphere, the homemade look and taste of the food and nostalgic design, are all aligned to create the warm and homey environment that Orlando envisions for his restaurant. Indeed, creating a social bond with his customers is at the heart of Orlando's philosophy which is summarized by the sign above the entrance: "May all who enter as guests, leave as friends".

“Food is just an excuse to be here...It’s a kind of relationship that some people don’t even have with their families.”

IRONBOUND’S IMMIGRANT CHURN

The closing decade of the 20th century and the early 2000s brought an influx of Brazilian immigrants to the Ironbound. Orlando and Silvana were two of them. Orlando immigrated from São Paulo, Brazil in 2000 with the dream of opening his own boteco – an informal bar that sells alcoholic beverages and appetizers. Initially living in Queens and working in Manhattan, he was attracted to the Ironbound by the prospect of work and the presence of a large Portuguese-speaking community. He soon found a job at Brasilia Grill, one of the first Ironbound restaurants where the property was owned by Brazilians, a big milestone for the Brazilian community which was accustomed to renting from the Portuguese.

“I left the train at Penn Station. Walking around, listening to Brazilian people speaking in the street, I thought, ‘Oh my God, this is my place!’”

Between Orlando's early days at Brasilia Grill and establishing his restaurant on Jefferson Street, the Brazilian population in the Ironbound nearly doubled, and so did the number of Brazilian restaurants. Similar stories lie behind many of these restaurants. Like Orlando, Farid Mubarak, who owns two Brazilian restaurants in the Ironbound, worked in several local restaurants before opening Casanova Brazilian Barbeque, in 1996. Thanks to the growing Brazilian population and a strong economy, within a decade after the opening of his first restaurant, Farid purchased a property at the intersection of Merchant and Clover streets and opened Boi na Brasa. At the new, larger venue he was able to include a parking lot, a dedicated bar, an upstairs ballroom for private events, and multiple studio apartments to house his newly arrived employees until they got settled in the neighborhood.

Sabor Unido has been a family operation since its opening in 2012. Responsibilities are pretty much divided across age and gender lines, and so are the restaurant's spaces. Orlando and Luiz preside over the dining room as if they were hosting a family gathering. Helen and Isabella, the two Brazilian girls that wait tables and assist Luiz and Orlando in the front, round out the public-facing staff, creating a coherent image of Sabor Unido as owned and operated by a Brazilian family.

Working the dining room, Orlando and Luiz seem to know everyone, and when they don’t they make it their business to introduce themselves and be on a first-name basis by the end of the meal. Luiz, is at the forefront of the scene; greeting customers, waiting tables, and bringing new ideas to the restaurant, while managing the online presence and social media for Sabor Unido. When it is less crowded, Orlando will often sit and chat with customers. Though Orlando's eighteen years' experience in the restaurant industry has prepared him for running the business, as they plan the opening of a second restaurant in New York City, Luiz's age and more intimate interaction with and understanding of American culture has become an important asset for expanding the family business.

Behind the scenes, the more recent immigrant history of Ironbound is on display in the kitchen which is Silvana’s domain, where she is assisted by Eduardo, the Ecuadorian dishwasher, and two Guatemalan cooks, siblings Miguel and Telma. The Brazilian family, who immigrated to the neighborhood less than two decades ago, now employs more recent immigrants from Ecuador and Guatemala. The Guatemalan cooks have learned to make Portuguese and Brazilian food for the same reason the Campos’ added Portuguese dishes to their Brazilian menu; resourcefully adapting to hybrid environments is essential for immigrants who are constantly navigating unfamiliar terrain.

Multi-ethnic foodscapes like Sabor Unido flourish in immigrant neighborhoods like Ironbound where restaurants provide an important source of employment as well as opportunities for both cultural exchange and social mobility. Sabor Unido, like many restaurants in immigrant neighborhoods, is a place where diverse communities make and break bread together. Over the last decade the largest number of immigrants arriving in Ironbound have been Spanish speakers. Like the Brazilians and the Portuguese before them they have turned to restaurants as incubators for entrepreneurial aspiration and cultural exploration. Perhaps Telma and Miguel will one day open their own restaurant. If so, it is likely that they, like the Campos’ and so many immigrants before, will require the assistance of even more recent arrivals than themselves to make it a success.

While the Campos family is now settled in Ironbound, the 2008 economic crisis chased others Brazilians back to Brazil where the economy was booming. With the U.S. economy now back on track, and a recent economic downturn in Brazil, many Brazilians are once again arriving in Ironbound. Some are even showing up at Orlando’s restaurant looking for work and advice, just as Orlando did almost two decades ago.

“Now with the Brazilian crisis again, people have started coming back. Almost everyday I have people here looking for a job.”

THE BUILDING AS IMMIGRANT INCUBATOR

While the Campos family looks toward the future they have also established ties with the recent history of the neighborhood by listening and responding to their customers. When Orlando took over the restaurant from the previous Portuguese owner, he designed a menu entirely based on Brazilian cuisine. It didn't take more than a week for him to realize that the Portuguese customer base was too substantial to overlook. The most recent restaurants and cafes that had operated out of the building had established the site as a destination for the Portuguese. In addition, the Portuguese Our Lady of Fatima church down the block had a profound influence on their clientele. Shortly after opening, Orlando revised the menu to incorporate Portuguese dishes.

The name and sign for the restaurant came from one of Orlando's customers who brought up the idea of unity between Brazilian and Portuguese cuisine. This also became the inspiration for the restaurant’s name. The English translation of Sabor Unido is United Flavors. The new sign took its cue from the same idea: a Brazilian flag and a Portuguese flag, held by two spoons spilling their contents into the middle of a big pot, where the flavors and cultures are mixed and united.

“Sabor Unido, which literally translates in English as united flavor; two cuisines in one place.”

The various businesses that have operated from this modest one-story building over the years are reflective of larger patterns of migration into and out of the Ironbound. While today the restaurant is run by a Brazilian family, and features many Brazilian dishes, the presence of Portuguese cultural symbols and cuisine is a reminder of the building's previous quarter century housing Portuguese restaurants and a cafe. Similarly, the Stars of David that adorn the entrance of the Our Lady of Fatima parish center adjacent to Sabor Unido are reminders of the early decades of the 20th century when the building was a Synagogue serving the small community of Jewish families who lived in the neighborhood.

It is likely that the kitchen and refrigerator space in the back of Sabor Unido are additions made when the first Portuguese café was established in the building. Our Lady of Fatima moved next door in the 1970s, and the first Portuguese café at 77 Jefferson opened shortly after. The cement blocks used in the construction of the addition contrast the red bricks of the exterior wall of a building that has housed several generations of immigrant entrepreneurs.

Beginning in 1930, and every day thereafter for about 30 years, Pasquale De Castro walked from his home at 100 Jefferson Street to his shop in the building Sabor Unido occupies today. Pasquale’s previous shop along Ferry Street was a short walk from his home, but the new location reduced his daily commute to under a minute. During the years Pasquale walked to work, nearby buildings along Jefferson Street housed an expanding immigrant population. The Italian owned Biondi’s butcher shop that preceded Pasquale's had also catered to this community.

Illustration by Sahar Hosseini

Hosting Sabor Unido is the latest chapter in the history of a building that over the past century has been a hub of immigrant interaction, cultural exchange, and ethnic succession in the neighborhood. The Guatemalan cook who serves Brazilian and Portuguese food, and the Brazilian family that preserves the Portuguese culture of the neighborhood with a São Paolo flair are connected to their Portuguese, Italian and Jewish predecessors through this building — this memory palace. Its history testifies to the central role successive immigrant communities have played in adapting to and shaping a neighborhood that has been Newark's place of entry for so many and for so long.

THE NEVER-ENDING STORY

Six months after our initial visits to the restaurant in June of 2018, Sabor Unido underwent a considerable physical alteration in response to the most recent cycle of migration into the neighborhood. The restaurant’s success had inspired the family’s plan to create a version of Sabor Unido in Manhattan that would appeal to a population that is decidedly more affluent and less immigrant than the Campos’ Ironbound clientele. When complications arose with financing the second restaurant the family instead redesigned Sabor Unido to reflect the current demographic changes occurring in Ironbound.

As Newark’s much-hyped “Renaissance” generates jobs and investment downtown, the population of the city is growing for the first time since the end of World War II. Bordering downtown Newark along the railroad tracks, Ironbound’s restaurants, proximity to Penn Station, and urban village vibe have made it a port of entry for the most recent migrants — young, urban professionals in search of the new Jerusalem, or at the very least the next Brooklyn or Jersey City. Residential development in Ironbound is transforming the neighborhood’s built environment and demographics. The renovation of Sabor Unido reflects the arrival of these new migrants; just as the Campos family and their staff reflect the previous 30 years of arrivals and the hybrid Brazilian-Portuguese menu and decor represents the palimpsest culture characteristic of multi-wave immigrant neighborhoods.

The restaurant’s renovation focused on two threshold spaces that reconfigure the family’s relationship with its customers. Where Sabor Unido meets the street, the new space attached to the facade enhances the visibility of the restaurant on the block. The protruding black frame and large windows that claim part of the sidewalk are hard to overlook. At night, when the purple light fills the space, it creates a seductive glow that is eye-catching from the street.

Inside, the large wooden counter, which had previously separated diners from the service areas in the back, was removed. The new small and sleek counter positioned at the very end of the room breaks down the traditional separation between the staff and customers, and makes Luiz and Orlando more accessible to diners. The result is a wider uninterrupted space that accommodates more tables, with a more contemporary look and more spacious feel. Gone too are the random decorative frames on the wall, replaced by new decorative tiles and plates that create a more cohesive visual narrative of the restaurant’s hybrid Brazilian-Portuguese cuisine and cultural identity.

Drag the slider to view a juxtaposition of the old Sabor Unido’s with the new, featuring a new counter at the end of the room.

Illustrations by Gulse Eraydin

The new appearance and spatial choreography of the restaurant signals a transition from a typical, traditional small Ironbound restaurant with a largely Brazilian/Portuguese clientele to a more contemporary venue with a broader appeal for a younger, largely professional and more ethnically diverse demographic. Sabor Unido still feels like a neighborhood restaurant, but the neighborhood is changing and the Campos family is changing with it.

The Campos family not only experiences the new pattern of population movement to and from Ironbound in its kitchen, but has also realized its implication for its restaurant business. The tone and spatial strategies in their renovation signals the waves of gentrification near them in the vicinity of Penn Station, Riverfront Park, and Ferry Street. In true Ironbound fashion, Sabor Unido, which initially adapted in deference to the Portuguese presence on the block, has pivoted again to reflect the latest group of migrants to arrive in the neighborhood. And so it goes in a neighborhood that continues to be defined by an ongoing process of cultural adaptation and rejuvenation.

“Lately I’m noticing that more and more Muslim people are moving into the area”